Is there a future for Globalisation?

The narrative behind the defenders of free trade

Germany and China occupied centre stage at the G20 meeting in Hamburg. They positioned themselves as the defenders of free trade while the US under President Trump was, and is, seemingly determined to bring down the post-war world order and start a trade war with China, Germany and possibly others. Both the European Commission and the German Council of Economic Experts have declared that a ‘Trump trade war’ represents one of the most significant risks to the world economy.

That is the narrative that has now taken hold. Self-appointed defenders of free trade assuming the moral high ground at one end of the field. Trump’s America as the villain occupying the opposite side. And nobody quite knows what will happen when battle commences.

That is the narrative that has now taken hold. Self-appointed defenders of free trade assuming the moral high ground at one end of the field. Trump’s America as the villain occupying the opposite side. And nobody quite knows what will happen when battle commences.The trouble with narratives, especially those that are intuitively attractive and represent our own views as being both right and virtuous, is that they easily take hold. They soon become the only way of thinking, creating a herd mentality that translates into a comfortable intellectual laziness.

The above narrative on trade and globalization has just one flaw. It is simply wrong. And we cannot afford to let it go unchallenged.

What are ‘free-traders’ really defending?

Let us start with who deserves the moral high ground.

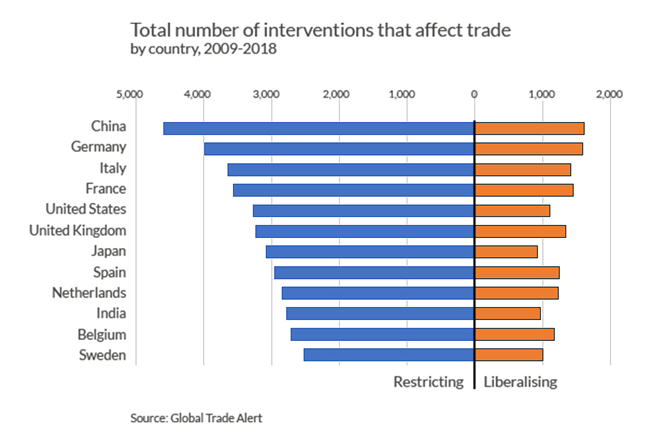

Germany and China have planted the free trade flag on their own soils and are waving it about with pride. But an analysis by Global Trade Alert has shown that, between 2009 and 2018, China and Germany have been the two countries that have implemented the largest number of restrictive trade practices (Figure). That ‘free trade flag’ soon starts to look a little bit frayed.

The reality is somewhat different. Among large economies, Germany and China have the largest trade surpluses. It is those surpluses that they are defending when talking about free trade.

The reality is somewhat different. Among large economies, Germany and China have the largest trade surpluses. It is those surpluses that they are defending when talking about free trade.The same mentality comes out from emerging markets. When people in emerging markets were interviewed about free trade, a vast majority declared themselves as being in favour. When then asked whether that meant that their countries should be open to significant imports from other countries, they disagreed. What they understood by ‘free trade’ was the freedom to export their own goods rather than reciprocal freedom to trade.

Similarly, China has, for decades, practiced what I like to call ‘free trade with Chinese characteristics’. Freedom to export accompanied by strict limitations on inward flows, forcing foreign corporations into joint ventures with local companies, demands for the transfer of know-how, constant appropriation of intellectual property, poor labour conditions as a way of maintaining cost competitiveness, and a manufacturing overcapacity that leads to dumping on global markets.

Germany, on the other hand, has consistently refused to use its savings and fiscal surplus to stimulate local demand as a way of encouraging imports. It has, together with the Netherlands, for years broken EU rules on the allowable size of its trade surplus while the European Commission has stood idly by. Its rules for doing business are among the most complex in Europe – something that some consider to be non-tariff barriers to trade.

Time for a new narrative

Given these facts, it is time for us to explore a new narrative. Here is one that I put forward simply to start the discussion.

The global trading system is broken. It is a politically, socially and economically unsustainable system designed for the 20th century and based on economic theories from the 19th century. Very little of it applies to a 21st century world.

Yet institutions are slow to change. And those who benefit most from any system will keep on defending it. Meaningful change only comes in times of crisis. It may take a credible US threat to bring the whole thing down to stimulate reform of a system that is no longer fit for purpose.

Is there any justification for this alternative narrative?

What has changed?

Much has changed over the last fifty years. And the pace of change will only accelerate. Here I will focus only of a few of the changes that have rendered our previous conception of globalization obsolete.

‘World trade produces net benefits for all’ was the 20th century mantra. Now it is clear that such benefits are very unevenly distributed with consequent economic, social and political implications. The free movement of global capital was seen as a vital fuel for growth and development. Now it is seen as a mechanism for financial destabilization, a system for hiding large amounts of illicit money, and a facilitator of tax arbitrage.

Low labour costs were seen as the competitive advantage of developing countries. Now they are seen as the basis of ‘unfair competition.’ Persistent unidirectional trade imbalances were dismissed. Now we understand their corrosive effects on deficit countries.

In an information driven world, privacy and national security issues affect trade – from the manufacturing of routers, to the security of data platforms, to building self-driving cars. For instance, Qi Lu of the Chinese tech company Baidu explains: "The days of building a vehicle in one place and it runs everywhere are over. Because a vehicle that can move by itself by definition it is a weapon.”

The 20th century culture defined human beings as ‘consumers’. We were all simply agents that drove growth through ever greater consumption. Economically and socially, consumption became defined as our reason for existence. Now many of us see ourselves as being more than mere consumers. And we have started to question how, in a finite planet, we can persist in equating economic success with ever more consumption and ever more growth.

Globalisation has driven, and been driven by, the rise of the multinational corporation. Economically, this was seen as a model of economic efficiency. Now many see the multinational model as potentially corrosive. Causing social upheaval as companies rapidly move employment from one country to the next in search of the lowest costs while leaving governments to clear up the resulting mess through the welfare system. Putting pressure on elected governments by playing them off against each other in investment, employment, taxation and lowering of regulatory standards. And coming to dominate markets through monopoly or oligopoly while competition authorities choose impotence over action in the vain hope that they are creating ‘national champions’.

But maybe most important is the major geopolitical shift. The post-war world order was characterized by Western dominance and overseen by the steadying hand of US hegemonic power. Now we have three more or less equally potent trading blocs – the US, China and its sphere of influence, and the European Union. Economists have known for decades that in such a structure, competition between blocs becomes much more likely than co-operation.

Some may see my descriptions above as over-stating the case. But nobody can deny that there is much truth in them. With such dramatic changes – and with more to come – how can anyone seriously argue that our global trading system must be preserved as is? That anyone who questions it and tries to change it is simply a wrecker of the global economy?

A system built on shifting sands

The whole edifice of free trade is built on David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage developed in 1817. Yes, you read correctly, 1817. It holds that a country has comparative advantage in the production of any particular good of equivalent quality when its marginal cost of production is lower than that of other countries. ‘Welfare’ is maximised when countries focus their production in areas where they had comparative advantage and traded with others where others had comparative advantage.

But we are now approaching the middle of the twenty-first century. The world has changed beyond all recognition. Yet the theory of comparative advantage still reigns supreme.

In Ricardo’s time, comparative advantage between nations changed only very slowly. The nature of the production of wine and cloth did not change dramatically in a few short years. The transfer of technology and know-how did not happen in months. There were not as many multiple definitions of ‘quality’ as there are today. There were none of the highly sophisticated marketing machines of today’s corporations that could magic up new definitions of quality and desirability from essentially similar goods. Ricardo’s underlying constraint of goods of equivalent quality therefore largely held true. And, of course, it was a world that traded largely in goods not services.

What do we do about all this?

The obvious next question is, given all of this, what should we do? Is it time to abandon the very idea of globalization and international trade and retreat towards autarky? No, it is not.

Policy solutions are available to start fixing some of the flaws that have evolved in the global trading system. What some such approaches might be, we can maybe explore in a future article. This time around suffice it to say that the real enemies of globalization are those who maintain that there is nothing to fix. Those who doggedly stick to the status quo because, for the moment, it happens to suit their interests. Those who keep trotting out tired and worn out arguments that are well past their sell-by date and are either too lazy or too unimaginative to explore alternatives.

Dr Zammit-Lucia is an entrepreneur and commentator on business and political issues. He is co-founder and Trustee of Radix, the think tank for the radical centre and co-author of "The Death of Liberal Democracy?” and "Backlash: Saving globalization from itself.”

Bitte senden auch Sie uns Ihre Meinung zur Zukunft der Globalisierung.

Gesellschaft | Globalisierung, 30.05.2018

Pioniere der Hoffnung

forum 01/2025 ist erschienen

- Bodendegradation

- ESG-Ratings

- Nachhaltige Awards

- Next-Gen Materialien

Kaufen...

Abonnieren...

03

JAN

2025

JAN

2025

48. Naturschutztage am Bodensee

Vorträge, Diskussionen, Exkursionen mit Fokus: Arten-, Klima- und Naturschutz

78315 Radolfzell

Vorträge, Diskussionen, Exkursionen mit Fokus: Arten-, Klima- und Naturschutz

78315 Radolfzell

17

JAN

2025

JAN

2025

Systemische Aufstellungen von Familienunternehmen und Unternehmerfamilien

Constellations machen Dynamiken sichtbar - Ticketrabatt für forum-Leser*innen!

online

Constellations machen Dynamiken sichtbar - Ticketrabatt für forum-Leser*innen!

online

06

FEB

2025

FEB

2025

Konferenz des guten Wirtschaftens 2025

Mission (Im)Possible: Wie Unternehmen das 1,5-Grad-Ziel erreichen

80737 München

Mission (Im)Possible: Wie Unternehmen das 1,5-Grad-Ziel erreichen

80737 München

Professionelle Klimabilanz, einfach selbst gemacht

Einfache Klimabilanzierung und glaubhafte Nachhaltigkeitskommunikation gemäß GHG-Protocol

Politik

Was ist Heimat?

Was ist Heimat?Der Philosoph Christoph Quarch betrachtet die Debatte um die Rückführung syrischer Flüchtlinge nach dem Sturz von Assad

Jetzt auf forum:

Profiküche 2025: Geräte-Innovation spart mehr als 50 Prozent Energie für Grill-Zubereitung ein

Sichere Abstellmöglichkeiten für Fahrräder:

Fotoausstellung Klimagerecht leben

Ohne Vertrauen ist alles nichts

The Custodian Plastic Race 2025

Niedriger Blutdruck: Wie bleibt man aktiv, ohne sich schwindlig zu fühlen?